- Home

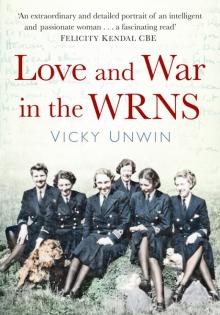

- Vicky Unwin

Love and War in the WRNS Page 2

Love and War in the WRNS Read online

Page 2

Sheila goes on a three-week domestic science course to prepare for being demobbed

Tom returns to London, having been demobbed

November

Sheila is still in Germany but preparing to depart for England

December

Sheila marries Tom Unwin in Durham on 23 December

Introduction

By the time of her death, aged 89, my mother had achieved her lifelong ambition: to be a respected member of the academic community. Recognised as the world’s expert on Arab chests and Swahili culture, following the publication of her book The Arab Chest (Arabian Publishing, 2006), she had been invited to lecture at conferences and symposia and basked in the late recognition of her talents. It was an extraordinary achievement for a Norfolk girl whose education finished with the Higher School Certificate and a secretarial course.

But what was it that transformed her from a gauche, air-headed and rather vain, even if clever, young girl, into an intrepid adventurer, archaeologist and a collector of African artefacts, who travelled solo around India, the Persian Gulf and Saudi Arabia in the 1960s and ’70s, like her heroine Freya Stark?

The Second World War proved to be a life-changing event for many young women, and for Sheila it was no exception. This collection of letters charts her rite of passage from childhood into womanhood. The letters sparkle with humour and observation, and paint vivid portraits of the hectic wartime social life – parties, riding, sailing, dancing – juxtaposed with gruelling night watches in both Egypt and Germany. Underlying this gaiety are undercurrents of mortality, combined with feelings of guilt at the forces’ opulent lifestyle, and her passion for her work, for instance her pride in helping to plan the invasion of Sicily under Admiral Ramsay, a man she held in the highest esteem. Her first-hand accounts of ‘The Flap’, the sinking of the Medway and the Belsen Trials offer insights from a rare personal perspective.

Finding love and a husband seem to have been a major preoccupation – she had at least three admirers on the go at any one time – and her 1946 whirlwind love affair and marriage to my father, a young Czech-born intelligence officer in the RNVR, also based in Kiel, underscores the desperation of many young women to emerge from the war with a ring on their finger, negating a return to a home life of suburban values and bourgeois boredom. The final letters on the subject of the wedding fascinatingly reveal the often hinted-at ambivalence of her relationship with her domineering and critical mother.

Sheila’s mother, Grace, the recipient of these letters, was one of ten children born to a middle-class Norfolk farmer, William Kemp Proctor Sexton (1847–1946). The family grew up in Downham Market; Grace, unlike her other sisters, did not marry immediately and, as was the way, became a governess/companion, to Canon Harris’s two children, Monica and Jack, from Appleby in Westmorland. The fate of her first fiancé is unclear, although I was always told that she sued him for breach of promise.

At some point, while travelling with the Harrises in Scotland, she became engaged to a quiet and well-educated Scottish captain from the Royal Engineers, who had been awarded the Military Cross in the First World War, but who had been heavily gassed. Invalided out of the army in 1922, he had the greatest of difficulty in finding a job – he sold dictionaries and vacuum cleaners among other things, much to his wife’s chagrin. Eventually they moved to Durham in 1938, where he was Deputy Controller of the ARP (Air Raid Precautions) and, later, secretary to the Durham County Hospital. As my aunt Rosemary said, ‘Daddy was never brought up to earn money.’ Indeed he was rumoured to be an illegitimate grandchild of the Sackville-West family, the most likely candidate being Lionel, 2nd Lord Sackville, who had a string of children with his Spanish mistress, Pepita, among them Victoria Sackville-West (b.1862), Vita’s mother.

This is quite possible: his father was born in Worthing in 1858 to Harriet Mills, and baptised William Thomas Greenland (Greenland being the name or, more likely, pseudonym, for his father). Sergeant Major William Mills married Helen Horn Findlay from Rhynie, Aberdeen, and together they moved with the army: first to Malta, where my grandfather Percival Findlay Mills was born in 1890. From there they set sail to join the regiment in Hong Kong, but William Mills died at sea two days out of Malta and was buried at Port Said (this strange coincidence was not lost on my mother when she discovered this fact in the 1990s). Helen and the young Findlay, as my grandfather was known, returned to Scotland, where a mysterious benefactor paid for his education at Edinburgh High School, before he joined the Royal Engineers as an officer. Quite an achievement for the son of a poor widow – unless he received help.

If you look at the photograph of him you will notice a great likeness to Vita Sackville-West, who was born only a couple of years later than him, in 1892. The mystery will never be solved, according to my mother, who spent years trying to track down her forebears. ‘I can only comment that he physically resembled Vita Sackville-West, quite strikingly so, and was tall, with a long face and large high-bridged nose. He was tall quiet and reclusive, and certainly no match for mother who was overbearing and strong-willed. No wonder he didn’t talk of his origins, which is annoying to us.’

Grace was a bossy, social-climbing bridge player, and in order to make ends meet she ran a boarding house in Glebe Avenue, Hunstanton (it had seven bedrooms and a live-in servant girl) which catered for summer visitors. During these months the girls were packed off to rich relatives. Two of Grace’s sisters had married well: one, Aunt Rose, was childless and was keen to adopt Sheila (but Grace refused to agree as it was not the done thing), and the other aunt, Dorothy, had three children and would take the two young sisters on holiday with them to Skegness, Scotland and, once, to Jersey. Sheila was very close to her cousin Hazel as they were exactly the same age; Hazel told me that Grace had a ‘terrible temper’ and used to hit Sheila, but never Rosemary. I believe Rosemary was jealous of this friendship.

Sheila adored her father, who was bullied mercilessly by his wife. Before the First World War he had been an employee of the Crown Agents and had travelled widely, including to Iraq and West Africa. He was an intellectual and I think she felt a great empathy for him and a solidarity born out of their shared victim status. Her occasional letters to him are warm, loving and more considered than those to her mother.

Both girls were bright, and attended Rhianver College; some of Sheila’s schoolbooks survive, showing a talent for painting and art – something that she was to return to in later life and, indeed, in the occasional sketches contained in her letters – in the beautifully executed and coloured drawings of historical and Shakespearean figures amid the copperplate writing. Both girls won scholarships to St James’s Secretarial College in London, where they went just before the outbreak of war to earn a living. Sheila excelled at shorthand and won the top prize of 140wpm, something she remained proud of for the rest of her life. Rosemary became secretary to the head of the department store Bourne & Hollingsworth.

Unwanted and unloved by her mother, bullied by her sister – Rosemary was pampered and adored – the sisters were never close. Sheila is frequently disparaging about Rosemary’s tardiness at joining up and loose behaviour: perhaps she was trying to get her own back? Little wonder she escaped and joined up as soon as she was old enough, just after finishing college and a month after her 18th birthday.

Knowing this, I wonder why she devotedly wrote to her mother every week until the mid 1970s: Sheila certainly never forgave her for her unhappy childhood and, later, for taking my father’s side in their messy divorce. This latent antipathy towards her mother surfaces occasionally as she chastises her for gossiping and not reading her letters properly. Her marriage to an idealist with no social standing in Britain may well have been a subconscious put-down for her mother’s snobbery.

And yet Sheila confides in her mother and seeks her advice, perhaps out of a particularly British wartime sense of duty that we find hard to understand today. Maybe the sight of all her fellow Wrens devotedly writing to their parents i

nfluenced her notion of ‘home’ during the six years she was away, and undoubtedly she wanted to make her mother proud of her, to prove that she was the more worthwhile daughter. She is homesick too, frequently reminiscing about England and the countryside, contrasting the heat and dust of Egypt with the cool, green fields of home.

And, like many members of the forces posted overseas, there was a real sense of guilt at escaping the privations of the war at home. Ever the dutiful daughter and feeling ashamed about the abundance and excess of food, fabrics, cosmetics and all sorts of items scarce in England, she devotes hours to buying basics and packaging up parcels home. Given the ferocity of the naval battles raging in the Mediterranean, and the frequent sinking of the convoys carrying supplies and mail, there are frequent anxious mentions of letters and parcels going astray.

There are small hints of her future social conscience and liberal ideas – she visits injured sailors in hospital and is horrified by the extent of the destruction and suffering of the civilians in post-war conditions in Germany. Her letters demonstrate a growing fascination with archaeology and gift for travel-writing. She paints vivid portraits of the Musky in Cairo, of visits to the citadel, the pyramids, the City of the Dead, its mosques and ancient houses, and of her excursions to Beirut, Damascus and Palestine.

I believe this whetted her appetite for her later forays into the early Islamic culture of the Swahili coast, where she participated in several archeological digs, and her lifelong quest to discover the origins of the Arab chest.

Her rather unhappy childhood explains her yearning to be loved and to be happy, and the dominance of affairs of the heart in the letters often seem to put her work in the shade. But careful reading shows that she took her work and the war extremely seriously and was proud of her contribution. Censorship will have prevented her from writing much of the detail of her work, but there is a real sense of the long hours and the exhaustion, juxtaposed with absolute necessity of living every moment.

To the memory of my feisty mother, Sheila, and my equally spirited daughter, Louise.

❖

Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o-er wrought heart and bids it break.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth

I have kept to Sheila’s spelling and punctuation, changing absolutely nothing. Sometimes this gives rise to inconsistency or some political incorrectness, but I wished to retain the letters’ charm and authenticity. Obviously I had to cut the letters down by about two thirds, nevertheless I think what remains gives a real flavour of Sheila’s war.

1940

‘Disappointed with it all’

My mother, Sheila Mills, joined the Wrens just two weeks after her 18th birthday. She had only just graduated from St James’s Secretarial College, and was working at Currey & Co, a law firm. By September 1940 the Blitzkrieg was in full swing; although the Battle of Britain had been won, London was suffering from air raids, France had capitulated, merchant ships were being torpedoed, Scapa Flow had been bombed, Italy had invaded North Africa, and the Axis – consisting of the Germans, the Italians and the Japanese – had been formed. Rationing had been in force since January. The future did not look bright.

To Sheila, as to many young people, it must have seemed logical to join up before being called up. In her case, as a well-educated girl with excellent typing and shorthand skills, she must have hoped for an early commission, something her letters reveal more or less from day one. Inheriting her father’s wanderlust and, with her childhood sweetheart, Paul, already a naval officer, joining the Wrens must have been a natural choice.

Nevertheless on arrival in Scotland on 1 October, the enormity of what she has done begins to dawn on her. Her first letters from Dunfermline are a childlike mix of excitement, impatience and apprehension, and reflect her middle-class upbringing and values inherited from her snobbish mother:

W.R.N.S Quarters

St Leonards Hill

Dunfermline

Fife

2.10.40

My dear Mummy and Daddy

This is my second day here and all goes well. So far! I went into the town last night and bought an enormous torch, then got lost and had to ask twice before getting home. The 3 other girls seem most kind and helpful. They all LOVE the Wrens, say they have a super time, and wouldn’t be out for the world. They seem to fraternise freely with all and tho’ not a fast type really, pick up all kinds of people!

Yes Mama, we have to wear knickers ‘closed in at the knees’ for the morals of the Navy must be kept up! Also we have to have ‘hussifs’ to keep sewing in. Could you please send me the sleeve I knitted and which I left behind – and also my pale nail polishes (thick and clear) as we can’t wear coloured polish. Hope I can use the Barbara Gould! I slept very well but was woken by furious snores from next door neighbour, which seemed strange after sleeping through all the guns of London. We had to get up about 7, had breakfast at 7.45 and then made our beds. At present I’m sitting in the rest room which is a huge, high windowed room, with wireless going. We’re on a hill and the trees look marvellous – everything is very bright and light. I’m expecting to be called at any moment to be told where I’m going. I rather wish I wasn’t a writer because you have to work from 9–6 every day, with one free day a week. As a telephonist, coder or a telegrapher you work half every day from 9–1 or 1–6, which seems much better.

Two rather nice girls have just spoken to me and they Signal. They work at C. in C. as I may do. They tell me they are going to be moved to some place or other where they will have to work underground. But then they have to work on during raids. Everyone seems terribly young. When they hear I type and do shorthand they think I’m most accomplished, which makes me laugh, and I feel quite a grandmother – at 20!

On top of this she is not impressed with her fellow Wrens:

… I’m told that most of the Wrens are nice but some are pretty queer. They all appear to be honest I’m told … They are very young, or about 25 or 40 and missed their chances! I’m afraid I must be rather blasé or a terrible snob because I don’t feel inclined to run around with any Tom Dick and Harry like these girls do. Any soldier or sailor does for them. But we shall see.

Please don’t think I’m wet blanketing it altogether; doubtless when I’ve sorted my friends and got my job sorted all will be well. People have been most kind, really, but they are terribly mixed. They keep coming and going, I believe, as this is a training and drafting depot.

Tons of love

Sheila

She is most amused to meet up with Miss Kidd, the secretary from St James’s who ‘remembered both me and R [sister Rosemary], that we had got scholarships and told the office, which may be useful. She also remembered we lived in Norfolk!’

Her work gets off to a rocky start, working in the Wren office part time and doing coding the rest. We should remember that this is only day 4, so she is showing an unreasonable amount of frustration and disappointment, probably exacerbated by anxiety.

This is compounded by an unpleasant incident soon after she arrives:

W.R.N.S. Quarters

St. Leonards Hill,

Dunfermeline

5.10.40

My dear Mummy,

I was reassured to get your letter and the papers. I had a simply horrid day and was feeling most depressed and they cheered me up no end. Yesterday I went to Mrs Henselgrew’s office and worked there a bit (she’s secretary to the Wren Superintendent) then I was transferred to coding which is rather fun but might be boring later on – not sure. Well I did that all this morning and then went to the Signals office (S.D.O) to help this afternoon. It was awful. All I did from 2:30–7 was file papers in pigeon holes. I nearly died of sheer boredom and fatigue for I had to stand up the whole time and had no tea at all. Then I had to go back to coding at the last minute as they were short. I don’t know whether I’m going to code for good, but some of the Wrens here are awfully jealous, because they applied for coding and were told it

was full and would they do telephone. This doesn’t make me very popular, as you can see. But I’ve met several people I do like. Two Irish girls, the O’Neils, from Newcastle (I believe they were receptionists at the Turks Head and another girl from Darlington. (Funny they should all come from Durham!) On the whole I hate the girls here – Mary Diamond, whom I liked at first, is most queer now, hardly speaks to me at all. Nancy is quite nice tho’. But a most unfortunate thing happened last night which I’ll tell you about.

We had a dance for members at the dockyard and Cochrane I. One horrible spotty man I was dancing with said he’d got some gin and lime and would I like some. I completely forgot Wrens and teetotal dances and said yes. Silly of me really, but I didn’t think. We were in a small room downstairs and unfortunately a girl I dislike saw us there. The sum of the matter was that Mrs Crawley found a whiskey later in that room, made enquiries, heard I had been there and sent for me. She was very nice, but I felt such a fool, especially as he wasn’t at all a nice man and on the face of it, it must have looked rather bad. I told her I had had gin and lime and she asked if I knew the difference between that and whiskey. Then she explained (!) why they mustn’t have drink at parties and what might happen if men got drunk and made me feel a 2 year old. She was certainly nice and told me she knew that I wouldn’t get up to tricks, and was surprised to hear such tales of me (!) but that she was afraid I might earn myself a bad reputation. Of course, I apologised and said how silly I was – inwardly feeling furious, both with myself and that stinking girl. I bet a ghastly tale gets round to all the people I don’t like, and they can be horrid I can tell you. However I may not remain here, but may be drafted.

Love and War in the WRNS

Love and War in the WRNS