- Home

- Vicky Unwin

Love and War in the WRNS Page 12

Love and War in the WRNS Read online

Page 12

I am having 2 frocks made – a chalk blue silk with white fleurs de lys on it and a green pin check cotton – very pretty. I am getting thinner, isn’t it marvellous. Have you heard any more of Paul? I am most anxious to know where he is and whether he has left his last ship. He might be coming out here you see. This place is looking gorgeous just now – most of the streets have trees on either side and the flame trees are just one mass of colour – a glorious vivid orange red – the bougainvilia [sic] is almost over, but these flame ones are magnificent. I wish you could see them – you can scarcely believe your eyes … I love my work – it is so terribly vital and important I really feel I am doing a good job, and it counter-balances the regrets one has of not being at home – Regrets? Of course we all have them, but they don’t necessarily make us unhappy – far from it! I’m now going to dash off to the Sporting Club to meet John for tea and then back to bed before night duty, which is from 1 am to 0830. Working all the time and if you get no sleep you feel AWFUL. I know – I’ve tried it! So heaps of love, now take care of yourself and don’t think this place is making me blasé or discontented – Just the other way round. It wakes you to reality – Sheila!

The war did indeed nearly come to Alexandria. On 28 June General Auchinleck gave the order to evacuate Alexandria and Cairo, to burn all papers, for the Delta to be flooded and for more defensive positions to be built outside the two major cities. Mussolini even flew into North Africa in preparation for the taking of Egypt, while the Germans dropped leaflets on Alexandria to prepare people for their arrival. The events of the end of June were termed ‘The Flap’, and at home came under much criticism for undue panic.

This was unkind as, for about a week, it was very touch and go as to whether the Eighth Army could hold Rommel and his forces from a final advance on Cairo. For many Egyptians, fed up with British rule of their neutral country and also with the high cost of living which had given rise to several strikes in 1942, a German victory was to be welcomed if the propaganda was to believed, and they rather enjoyed the sight of the British queuing round the block to raid their bank accounts, and the mayhem at the railway station as women and children were sent to the safety of Palestine and Luxor.

The following letter, describing The Flap and Sheila’s own evacuation, was written in September, when the censors would allow it. It also shows that despite her relative lack of education she had keen powers of observation and a writer’s eye for detail and humour. It is the first of many descriptive letters that she sends from Egypt and, later, Germany:

Office of C in C Mediterranean

C/O GPO London

27th September 1942

My dear Mummy –

I haven’t written you a proper long letter for ages, and ever since we came back from Ismailia I’ve been meaning to tell you about our ‘evacuation’, but thought I’d better wait a bit before I gave you a detailed account of it!

Well, we had been working normally for quite a long time at Navy House, which was rather a ramshackle old building standing in its own grounds by the side of the harbour and everything had been carrying on as usual – We’d had a Malta convoy to cope with, which meant a lot of doubling up watches, and of course we’d been told to expect a push in the desert in June, but as ever, nobody thought a great deal about it and were far more concerned with our convoy, which after all, was a Naval operation. These convoys, I may add, are one of the most exciting bits of our work, as we direct one portion from Alex, and every signal we send out is vital and terribly important. So the push came, and at first we did extremely well – everyone was very confident and pleased. Then things began to change a bit, and it became apparent that Gerry was moving in the wrong direction. Every army signal from the desert was received with great excitement and not a little trepidation, and of course everyone was discussing what they thought would happen. I personally have, and always will have, great faith in the army, as I have met a lot of grand people in the army out here and know that there must be thousands more like them. However, things came to such a pitch that plans for the precautionary removal of Naval units from Alexandria were formed, and on the 28th of June, it was decided that we should move. But we weren’t told anything definite, and although we knew what was in the air, beyond packing one’s vital garments etc. there was nothing to do but wait and see.

That day I was working all morning, and was supposed to do an all night. Just as Margot and I left the office we were told it was possible we were going to Port Said that evening, but were not to breathe a word to anyone. So we returned to 11, Rue Rassafah, where I found Esmé Cameron, a great friend of mine who shared my room, packing like mad for herself and Audrey Coningham, who worked with her, and off she went at half past two. Then I discovered other people had already gone, but still no word for us. We sat around all the afternoon, Mary Dugdale, Rachel and I, and others whom I can’t remember. We idly packed, wrote letters home (one of which I found the other day) ate an enormous tea, and censored a huge basket full of Wrens’ letters, which we thought might get left behind if we rushed off in a hurry. I can remember Mary playing and replaying a rather wizard record of Richard Tauber singing ‘all the things you are’ – time and time again, I thought everyone would create hell, but luckily, they didn’t seem to notice it. In the middle of all the turmoil a man who had seen John Pritty in Cairo arrived with a letter for me from him – I tried not to show that we were on the move, and think I succeeded because when he saw John afterwards he said he didn’t know that we had moved.

Eventually Mary and I got bored, so we took to hurrying into town, as she had to collect some laundry, and we also did a little odd shopping, bought chocolate and biscuits and so on in case we had to go. We returned for dinner at seven to discover that things really had come to pass and that we were to go at 1015 that evening on a special train to Port Said. We rang up and booked seats, but of course weren’t able to get a taxi for ages, and we all had at least 3 pieces of baggage, odd tennis racquets and so on. However, we did get one, and then there was journey after journey of 2 people plus baggage, and one returning with the car in case the driver ran away. Johnny Rathbone, who was a survivor from the Malta convoy [her friend Roddy’s husband, who lost everything when his ship went down] and who was staying in the officers’ rest house next door was my salvation – he appeared out of the blue to say goodbye to me, as he was off to Durban the next day and seeing me plus an enormous amount of baggage still on the doorstep at 10 o’clock, found another taxi from nowhere, and off we set with about 3 minutes to catch the train in. When I and my baggage were eventually disgorged from the taxi and flung onto the crowded platform, to my horror I saw the train slowly sliding out of the station! That was such an anti-climax that I decided there and then to wait till the morning and leave at six am. However, it was not to be so. Everyone seemed to take the most kindly interest in me – a Naval Commander patted me on the back in a fatherly way and told me not to worry and various sailors and soldiers made jokes about the last train to Munich. Just as I was deciding to spend the night in the cloakroom with all the baggage, up rushed the R.T.O. [Railway Transport Officer], an army Captain, a gunner I think. Without more ado, I and my bags were tossed into a 15 cwt truck, and with about six Naval ratings, we just tore through Alex down the Aboukir Road, to Sidi Gaber, where the train was making its next stop. All speed limits were thrown to the wind (and almost my hat as well!) and do you believe we arrived there about 5 minutes before the train.

When it eventually stopped in the station, the R.T.O. made a dash for the C in C’s coach (reserved specially for us) and, on finding all the doors locked, told me I’d have to be hoisted into the carriage. There are no glass windows, so it was fairly easy. So in I went, and was given quite a welcome by 3 Naval officers, 1 large wolfhound dog, and the fleet chaplain. The bags were thrown in after. When we eventually settled down, all in the dark, the dog, Jasper, made its home on me – and we proceeded to try to sleep. We could see some kind of an air raid taking place

over Alex, but couldn’t tell whether it was bad or not. It was a brilliant moonlit night, and about every quarter of an hour we stopped at some small village and people climbed in and out. There was no sleep for us – me, anyway!

I should tell you that the parts of my equipment I really needed – haversack with food, water (it was terribly warm) washing materials, and my great coat, etc. had gone on with one of the first batches, and the train was so crowded it was impossible to move out of one compartment. Eventually we stopped at Santa, and the man who was sitting next to me discovered that his wife, baby, nurse and 19 pieces of baggage were in the carriage next door. He had to leave them to come away and had no idea they had been able to make the train. I remembered later they had caught the train at Sidi Gaber as I did. Everyone was terribly thirsty and we had most amusing bargainings for melons and eggs and lemonade (all of which it is madness to eat, as water can so very easily be tainted in this country).

However, we arrived at Banha, where we were told we were to be shunted into a siding and would stay there for six hours. It was there that I remet all my friends, who were very worried about me – they had had an awful time having got into the wrong coach and had had crowds of squealing wogs [a commonly used term in the war, possibly standing for Western Oriental Gentleman] yelling at them – in the end 2 N.O.s just arrived in the country, mounted guard outside their carriage – but it was awful for them, as they were 9, plus baggage, in one small compartment.

All my carriage, except the fleet chaplain and I, removed themselves temporarily, and with great enterprise. The chaplain produced a bottle of lime, (which turned out to be far more gin) which we shared, and offered me his cassock to sleep in, as it was then about 2am and rather cold. So I slept till about 6:30. When I woke up with sun pouring in the carriage and everyone saying what a marvellous breakfast they had had at a local cafe for the forces – The Victory. So he and I got out and ordered an enormous meal of omelette, tomatoes and chips and tea. My goodness, it was marvellous, then off the chaplain sped and bought the most enormous melon I have ever seen, and a huge bunch of grapes all fresh and with the bloom still on them. On returning to the carriage, I found Pip Pritchard, another Wren Officer, installed. She hadn’t been feeling well and was swathed in blankets and sheets and surrounded by pillows.

Soon we were on our way once more, but huge smuts kept blowing over me and I was filthy. We arrived at Ismailia, and Mrs King, plus baby, nurse, baggage and so on separated and on we sped to Port Said. We were now surrounded by horrid yellow sand, and the Suez Canal on one side. The wind from the desert ride was so hot that we had to shut the windows. Occasionally we saw a ship in the canal, which was terribly calm, and much wider than I thought it would be. The melon was a godsend. We cut it in pieces with a razor blade, and I have never loved one more.

So we arrived at Port Said, the heat by this time was tremendous, and it seemed ages before we had sorted out our baggage and travelled in a huge lorry to the YWCA. This was a flat on the very top of a tall building overlooking the sea – it was so cool and peaceful and we were soon installed. That night just as I was getting to bed, someone came in to tell me Esmé Cameron was downstairs the poor girl had had rather a dreadful time, had only the clothes that she stood up in, and had lost all her possessions [she had gone down with the Medway, recorded in a later letter, when censors would allow]. I had never expected to see her again so soon.

The next day Rachel and I trooped round Port Said, which I liked. I sent you a cable, and then we went to Navy House to see about a case of mine which had vanished. By that time Wrens were arriving from everywhere, by sea as well as by land, and when we returned to the YWCA. I was detailed to go to a convent and see about setting up beds for 40 Wrens. So into a gharry I jumped, and away to the convent, where I found about 20 Wrens already installed, large numbers of nuns who spoke no English and some Gyppo sailors. Between us we managed to erect about 35 or 40 beds in a huge room right at the top of a tall building, and arranged all about lights, bathrooms, showers etc. This ended with a complete tour of the roof and the school, as all the bathrooms, showers and lavatories appeared to be stationed up there – speaking French the whole time! It really was terribly funny, and I thought how much everyone would have laughed if they had seen me.

In the midst of all this (I had asked for tea to be prepared for 20 Wrens and those who were in had eaten the lot, so more chaos ensued!) I was phoned up by Pip, who said I must go back to the YWCA immediately, and she would carry on. So off I went, once more in a gharry and arrived just in time for a well earned cup of tea. But alas, my days in Port Said were numbered, for I was told to pack immediately and drive down to Ismailia in a lorry to be there in an hour’s time! This meant packing for Renee and Rachel too – the former being missing, and the latter having to rush out to a laundry to collect a bundle of filthy clothes we’d left there in the morning. In about half an hour Margot, Rachel and I were ready and boarded a huge lorry crammed with trunks, bags and N.O.s and we set off at high speed for Ismailia. The road runs by the side of the Suez Canal and it’s about 40 miles. The sun was setting and it really was a grand trip. Soon we knew we were approaching Ismailia, as we saw a lot of pine trees in the distance, and in a short time we were driving through avenues of trees with some grass growing by the sides of the Sweet Water Canal and everywhere looking almost English. Ismailia is a very green town – with grass squares, trees and palms everywhere – such a pleasant change after our dreary, dusty journey. We reported to Navy House, and were then taken to the YWCA which was just grand. A modern house belonging to the Canal Company, with a green garden and the most charming people running it. Mary Dugdale and Kay Way were already there as well as a lot of other Wrens, so we had many joyful reunions.

Rachel and I tossed up for which watches we should do as one was wanted to go on at 8.30 that evening and one at 1am. In the end I did the all night, sleeping most of the time on an arm chair. I think I could have slept anywhere!

And so our life in Ismailia began; it was terribly hot, and I have never worked in such dirt and heat in all my life, nor have I even felt so tired. But I loved it all – just one main street, with tiny shops either side, and the second storey coming out over the pavement, with pillars to keep it up, so that when you went shopping you were in the shade the whole time. Of the rest of our life in Ismailia I think there remains nothing to be told. We were there till the 8th of August, when most of the C in C’s staff returned to Alexandria, including the Cypher Officer.

There has been quite a lot of controversy here as to whether the Navy’s lightning move was justified or not. The RAF and the army rather tease us about it all, but I personally (and a lot of other people think the same) think that it was a wise step, because, if something unforeseen had occurred and we had not been prepared, events would have taken a very critical trend. Of course, there were many things which could have been organised better, but this is to be expected in any move of this kind. I think the people in Alex were completely shattered, or they say ‘so long as the Navy is here, we are all right’. All the nuns in the convent here were weeping and I really think believed Jerry was on their back doorstep! Naturally they were delighted to see us back again.

I think probably this tale will make you smile quite a bit, it did me tremendously, because all the time I couldn’t feel I was taking part in a real evacuation, and that one might see a German tank pop round the corner – as some people did. (They were 90 miles away actually) Actually we had far the best time of anyone – a great many of the Wrens travelled from Alexandria to Suez in cattle trucks, stopping by the wayside at regular intervals so that they could spend pennies. On one occasion a number of Wrens plus the wife of one of the N.O.s, got left behind and the train sped on without them. Poor Diana Booth was in hospital at the time with tonsillitis, and was taken to Palestine by hospital train. When she arrived there, it turned out to be Scarlet Fever, and she had to spend 6 weeks in hospital the only woman patient among hundreds of men

.

So you see, we do see life!

I don’t think I have said anything in this letter which wouldn’t pass the censor, and anyway, when you get it it will be very old news. However, maybe you’ll treat the matter with ‘some reserve’ and not tell the tale at every bridge party you go to!!! Please don’t throw this away, as it’s one of the longest letters I’ve ever written and I should like to read it over again when war is over!

With heaps of love to you all. You’ll gather from this that the Navy takes good care of us!

Sheila

In early July, Sheila’s parents were unaware that she was part of the evacuation and that her letters until 8 August are in fact written from Ismailia, although she is careful to let nothing slip. It might explain why Sheila gets so particularly annoyed at her mother’s misaddressing the letters, as it will result in them taking far longer to reach her. She realises they must be worrying about her and tries to reassure them. She is also concerned for Paul who, she assumes, must also be anxious. She must have been desperately worried for John and Robin, and countless other friends, who were all in the desert:

Office of C in C Mediterranean

c/o CPO

London

1st July

My dear Ma –

I have just sent you a cable saying that all is well and that you are not to worry. The Navy always turns up trumps and is certainly doing so at the moment!

So please do keep writing to me at the above address – as I think I asked you to before – not NILE, as I have never been based on them, and it takes much longer. Letters are surer to reach me if you put C-in-C on them. We are still thoroughly enjoying life – not in the same manner, maybe – but it is all great fun. Our only concern is for you all at home, who, I am sure, are imagining all kinds of silly things which are quite untrue. I have kept writing as usual, and sent 2 cables just lately, so I hope you realise that all is quite well. I am so sorry for those poor boys in the desert – it must be hell for them.

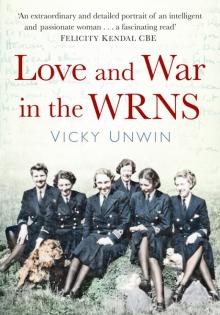

Love and War in the WRNS

Love and War in the WRNS